The Power of Normalization and Business as a Counterforce

by Emma Dunlap, 2022 Business Fellow

Prior to my experience through FASPE, I tended to think that business is inherently inclined to be, or at least to appear, neutral on social issues. I believed that this needed to change, but my vision for corporate activism was incomplete. I was somewhat wary of expecting businesses (given their incentives, responsibility to shareholders, etc.) to “fill the gap” when government fails to uphold fundamental rights. In addition, I focused on leadership and top-down processes of setting ethical standards, rather than contemplating corporations as entities composed of individuals with their own ethical inclinations and misgivings. FASPE allowed me to examine the role business plays in society, particularly during tumultuous times. It enabled me to explore how context and normalization influence decision-makers and who stays silent and who speaks up.

My FASPE experience challenged me to consider specific components of the Nazi era: the process of normalization, the role of business leadership and the individuals who enabled the Nazis, and the complicity of bystanders. Now, I am more certain that we should expect and embrace some level of corporate activism; otherwise, it is easy for companies to accept narratives that reinforce bigotry and to disavow responsibility. During the program, the business fellows explored the consequences of companies perhaps viewing their role as neutral, beholden only to profitability and economic concerns, either by accepting the Nazi system as normal or directly supporting the regime. These businesses were made up of people whose ideas and decisions affected the situation. At the German Resistance Memorial Center in Berlin, we saw how many Germans did resist the Nazis in various ways; however, the majority of individuals did not. Bystanders implicated themselves by remaining silent. Having reflected on this inaction, I began to ask myself how such people could come to accept, rather than protest, their world, and how I could apply these lessons to ethics in business today.

Some of the program’s topics I found most intriguing were the ideas of normalization and indoctrination. Normalization, or how normal such hatred and violence became, echoed throughout our readings, lectures, and site visits. Nazi leadership was strategic in implementing their agenda incrementally, taking an initial step (such as with the program to kill disabled children, Aktion T4),1 seeing how the German public reacted, and then progressing or adjusting accordingly. Incremental action, indoctrination, and financial and individual incentives furthered the process of normalizing a society built on the persecution, plundering, and murder of particular groups of people. Prior to FASPE, I thought of the Nazis as a cohesive, impassioned majority associated with the images in Triumph of the Will: imposing displays, marches, and book burnings. My FASPE experience challenged this perception and re-directed my attention to people who accepted this new reality as “normal” and lived their lives accordingly.

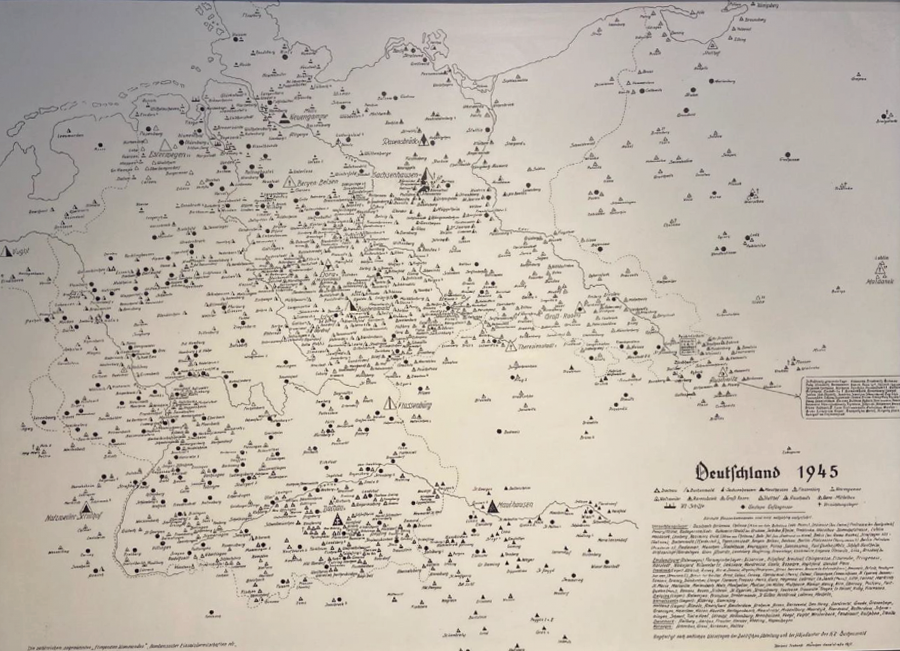

The impact of normalization and of bystanders was palpable when we visited the Sachsenhausen concentration camp outside of Berlin. Our tour guide told us that after the War, when questioned about their knowledge of concentration and death camps, Germans commonly responded that they were unaware of what was happening. Seeing firsthand that houses of Germans pressed up against the walls of Sachsenhausen, their response seemed implausible. Similarly, at the German Resistance Memorial Center, our tour guide also noted that Germans often said that they were unaware of the atrocities being committed. He directed us to a display that mapped over 1,200 concentration camps in 1945. Considering the sheer number of camps and their proximity to towns and villages, it is difficult to imagine a scenario in which people did not know.

Our tour guide at the German Resistance Memorial Center mentioned that after the War many Germans routinely said that there was nothing that they could have done to prevent the Nazis from carrying out their crimes. The memorial, in part, exists to counter this notion: to demonstrate that there were Germans who did something. These were people from different backgrounds and of different opinions who had disparate reasons for resisting the regime. I was struck by the story of Otto Weidt, a business owner who attempted to protect his predominantly blind and Jewish employees by forging documents, hiding people, and bribing the Gestapo. Weidt’s story contrasted with that of Topf and Sons, the engineering company that provided crematoria equipment for Auschwitz and other death camps. FASPE challenged its business fellows to think about these players in history who are left out of the mainstream narrative, both those who protested and those many millions who did not. I now think about these historical figures: the truck driver who brought people to the “euthanasia” center, the train conductor at Platform 17, or the up-and-coming fashion designer—business professionals who directly provided the infrastructure or did nothing to resist, enabling the Nazis to inflict immense suffering and destruction.

When I see decisions on contemporary issues that I consider unethical, I notice that my FASPE experience has reframed my expectations of businesses. Three weeks after I returned from Poland, the U.S. Supreme Court stripped people with a capacity for pregnancy of their rights, did away with a century-old firearm regulation during a gun violence epidemic, and vastly limited the U.S. government’s ability to regulate emissions while we are on the brink of climate devastation. Regarding reproductive rights, I have been enthused by some businesses’ willingness to fund additional healthcare and travel expenses; however, I expect a more robust response from across the private sector to counter the effects of these decisions. When issues directly affect the economic access, privacy, and health of your employees, your community safety, and the planet, silence is not an option. I hope for more universal, outright statements from business leaders condemning the ruling, a commitment to covering expenses for those affected most (such as contractors and hourly workers), lobbying, donations, and more. It is equally important that individuals, not only leadership, speak up and do so often. We need people who can see beyond the context of what has been normalized and call others’ attention to wrongdoing.

While I have always felt that social responsibility in business was important, I now see it as integral; I see companies as potential leaders in change, companies that themselves can be spurred on by the passion and vigor of the individuals who make them up. In this way, we can fight against normalizing wrongs.

Emma Dunlap was a 2022 FASPE Business Fellow. She is a management consultant at Accenture.

Notes

- Bergen, Doris L., War and Genocide: A Concise History of the Holocaust (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016), 127.